MAGNUM FORCE (1973)

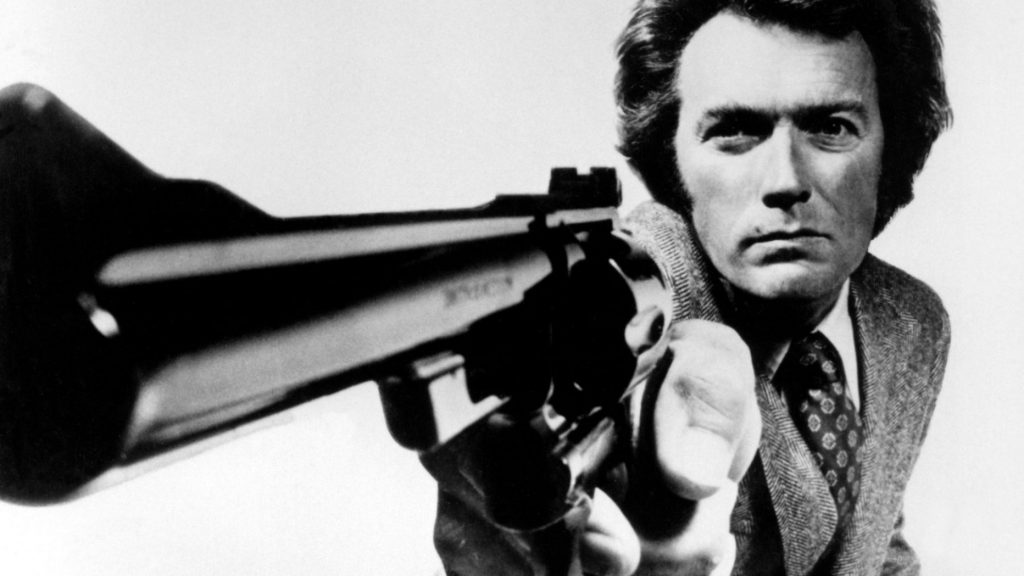

“I hate the —— system! But until someone comes along with changes that make sense, I’ll stick with it.” – Harry Callahan

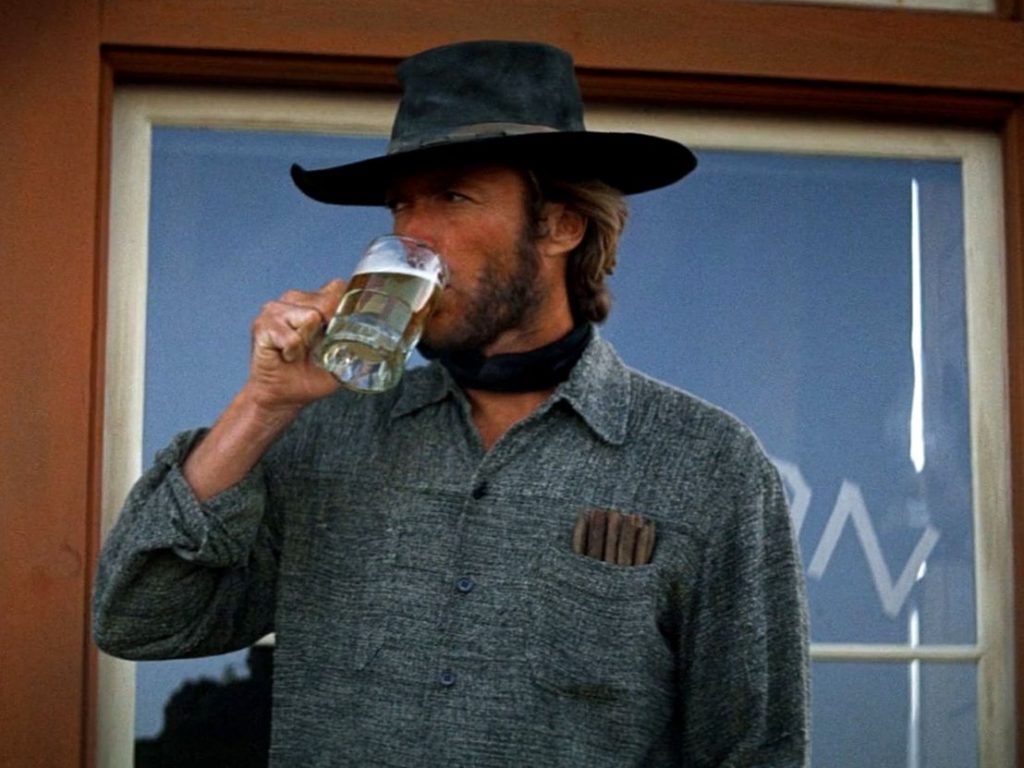

It was barely two years after Dirty Harry that Eastwood would strap on the signature .44 Magnum once again as Harry Callahan in Magnum Force. The results can’t help but be measured up against the original, in both positive and negative ways.

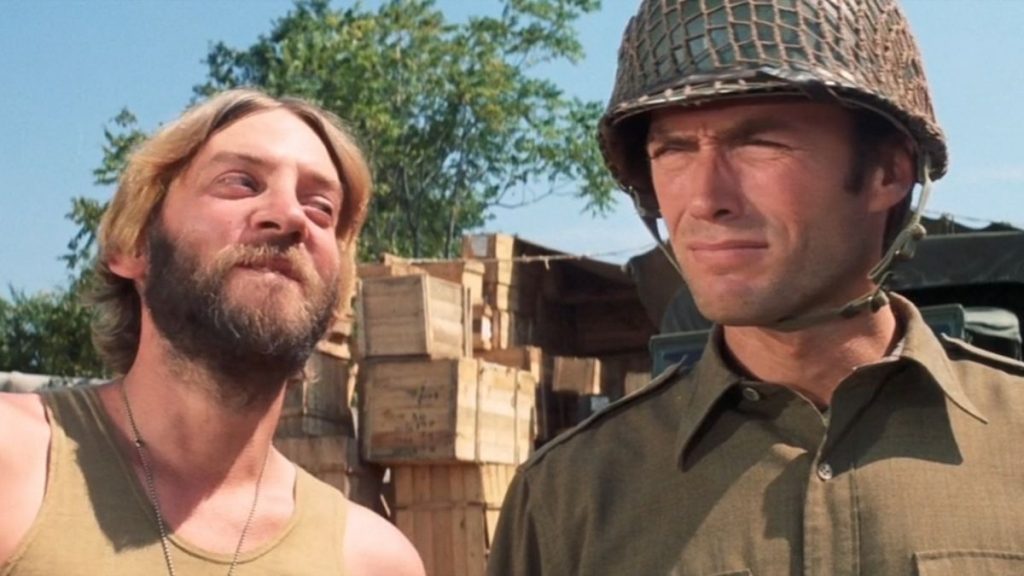

Picking up sometime shortly after the events of Dirty Harry (a fact only identifiable by a single reference from Harry about his last partner), Harry Callahan (Eastwood) has been relegated to stakeout detail by the stubborn and irritable Lt. Briggs (Hal Holbrook). However, someone in the city is taking justice into their own hands by murdering accused criminals who escaped the system through wealth or technicalities. When the evidence begins to point towards a group of vigilantes on the police force, Harry determines to uncover the truth and bring them to justice himself.

The film was largely an extension of unused material from the first film and a response to some of the criticisms and controversy that film generated. Eastwood wanted to make it clear that Callahan’s character was not a lawless vigilante, so building upon an idea first introduced by Terence Malick into his version of the Dirty Harry script, a script was commissioned by future director John Milius, with eventual rewrites by Michael Cimino. Eastwood was offered the director’s chair, but declined, which was a puzzling choice given what would become on-set tensions between he and Ted Post, someone who had directed Eastwood multiple times on Rawhide and had helmed the solid western Hang ‘Em High.

The final film caused considerable tension among its creators regarding the finished product. Writer John Milius all but disavowed it, citing the changes to the final act and the heightened violence from his original drafts as veritably ruining his original intentions for the story. In addition, director Ted Post cited multiple conflicts with Eastwood, who he claimed was frequently disputing who was truly in charge on set. Post accused Eastwood of exerting ego and leveraging control on set rather than allowing him to do his job. When the two of them had last collaborated, Eastwood’s star was only just rising in America and his directorial confidence didn’t exist yet. Although Eastwood himself had actively turned down the director’s duties for Magnum Force, it would appear that letting go of the role was harder than initially expected. Post and Eastwood would never work together again.

When viewed on its own merits, Magnum Force is a perfectly entertaining police thriller. The performances, particularly by Eastwood and Holbrook are strong as well as a solid showing by Felton Perry as Eastwood’s new partner. It also features a who’s-who of sorts for soon-to-be stars of the 70s including David Soul, Tim Matheson, and Robert Urich. It also effectively highlights Harry Callahan’s skills as a detective, something the original film didn’t emphasize as much as his boldness or attitude. In direct contrast to the vigilantism of which Callahan’s character was accused in the original, there is a deliberate and occasionally heavy-handed emphasis in this film to show that Callahan IS a part of the system and has no tolerance for predatory vigilantism (I’ll leave it to others to determine the level – if any – of hypocrisy at play in these assertions).

What’s sadly missing, unfortunately, are the strong senses of style and suspense that Dirty Harry had in spades. Magnum Force, for all its narrative merits, feels very paint-by-numbers stylistically. This isn’t wholly unexpected when considering that the bulk of Post’s directorial work had previously been for television, where a somewhat formulaic template might be seen as a necessity of continuity. The film’s major reveals will largely be guessed long before they are revealed, making their ultimate result feeling rather inevitable as well, which undermines the suspense factor.

There would be three more sequels in the Harry Callahan world, all of which would suffer from the common sequel problems. But as far as sequels go, Magnum Force isn’t bad. Eastwood even later cited it as his favorite entry in the franchise (which is interesting given that Eastwood eventually directed one of them). If you’re hoping to experience the same level of fascination and compelling storytelling that Dirty Harry brought, you’ll likely be at least slightly disappointed, but if you’re feelin’ lucky… give it a shot.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.