Ever since “the man with no name” rode through Sergio Leone’s haunted western territory, Eastwood seemed destined for greatness. His early filmography is populated mostly by westerns and cop thrillers (including perhaps his most signature role as “Dirty” Harry Callahan), with a few odd exceptions that would hint at some truly interesting things to come.

Having made this chronological journey through the first third of his filmography, I wanted to take a brief beat to examine some of the trends that emerged and identify some elements that defined the early period of his film career. There are absolutely elements deserving of praise, but also some disappointing trends as well. So, speaking in broad terms, here’s what I learned watching the first twenty films in “The Evolution of Eastwood”…

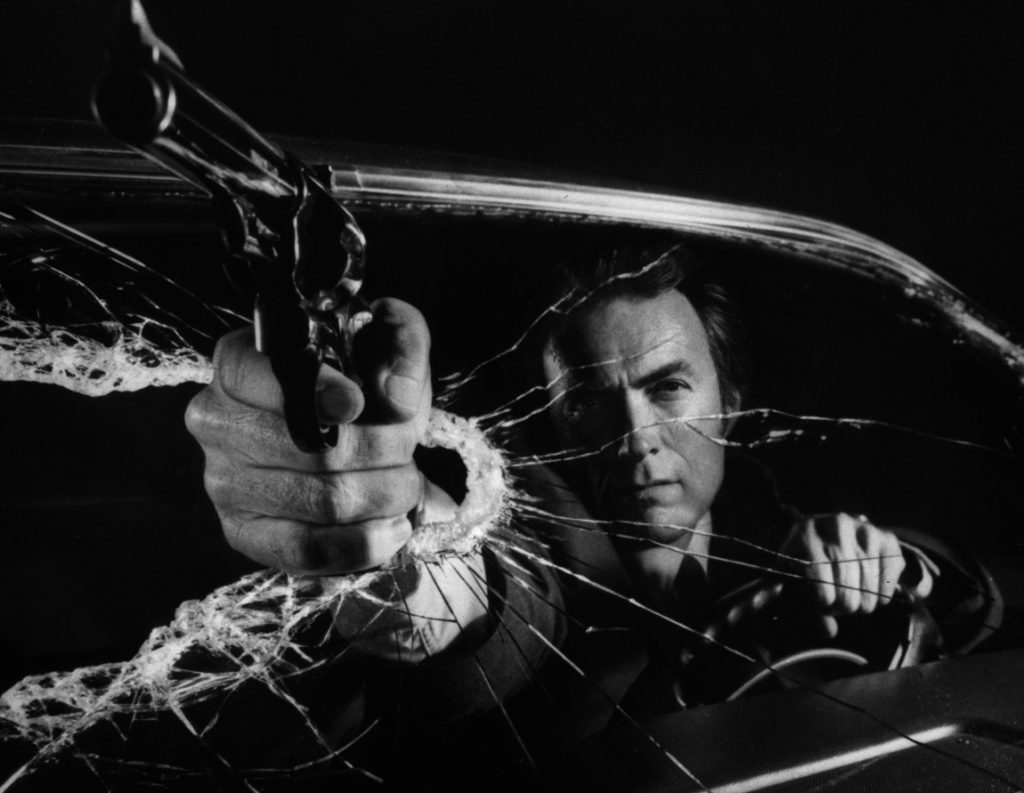

The Embodiment of Tough

One of the most common elements in each of Eastwood’s first twenty films is that he’s one intimidating s.o.b. His trademark squint (which first emerged as an accident due to lighting on the set of A Fistful of Dollars) would come to represent that steely, cold iron that apparently serves as a spine to each of his characters. In every single film, Eastwood’s character never loses a one-on-one fist fight (or gunfight for that matter) and the few times that he is subdued, it’s because of a multi-man ambush (for which he always doles out revenge). There are only two times in this early track in which Eastwood plays a remotely vulnerable character against whom the odds are sufficiently stacked. And, ironically, in both cases his opponents are women.

Misogyny Overload

I’ll not mince words here – in both his films (and apparently his personal life) – Eastwood doesn’t have a very upstanding reputation with women. His personal life is littered with numerous rumors of affairs (and an undetermined amount of children) and some of the authenticated details of his longer-term relationships don’t paint him in the best light. That sensibility makes its way into most of his on-screen personas as well, as he frequently seduces or coerces women into lovemaking only to treat them with rather questionable dignity afterwards. In High Plains Drifter, he outright rapes a woman in the first fifteen minutes of the film (a narrative element that is in direct alignment with the tone and theme of the film, but is disturbing nonetheless). It is interesting to me, then, that two of his stronger and more compelling films (Play Misty for Me and The Beguiled) feature him playing a character at the mercy of powerful (but unfortunately crazy) women. Both of those films represent strong pieces of filmmaking and strong performances from Eastwood, but it does little to dilute the already misogynistic trends in his early filmography.

Two major exceptions here is Shirley Maclaine’s turn in Two Mules for Sister Sara, which features a strong and resourceful woman, and Kay Lenz’s portrayal in Breezy (which Eastwood actually directed without starring in it). However, in both films, despite the maturity and actualization of the Maclaine’s and Lenz’s characters, they still fall for men who are of at least moderately questionable character – and who still exhibit disappointing attitudes towards women. These criticisms could be hurled as much at the sensibilities of the era in which Eastwood rose to fame as they could at Eastwood himself (more-so probably), but when taken in large chunks of viewing like this, the trends are hard to ignore or excuse.

A Question of Ethics

One of the most compelling and fascinating elements of Eastwood’s filmography is the consistent exploration of questionable ethics and morals. From his very first feature film (A Fistful of Dollars) through his dramas and thrillers, he is constantly exploring characters with foggy boundaries dividing right from wrong.

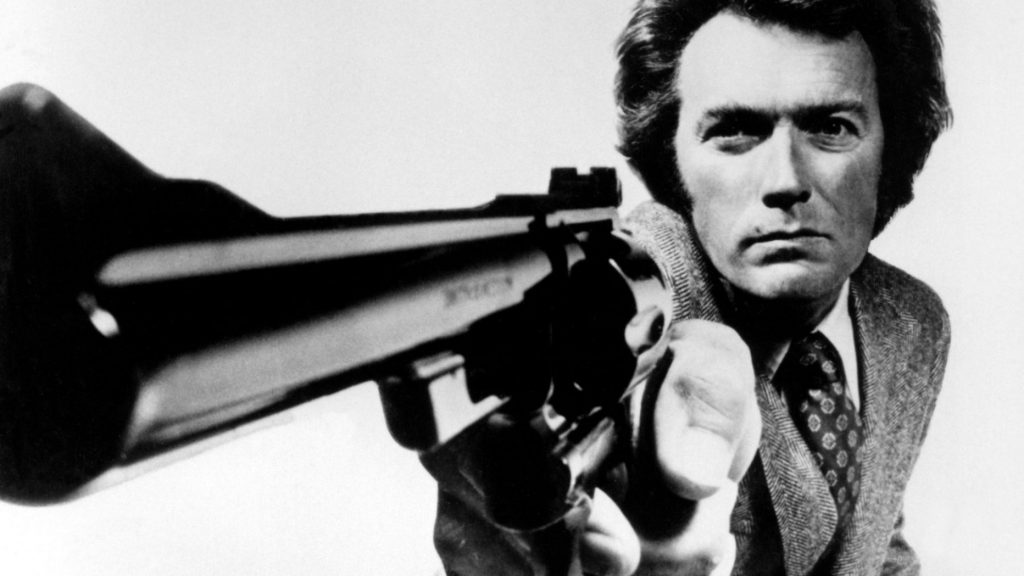

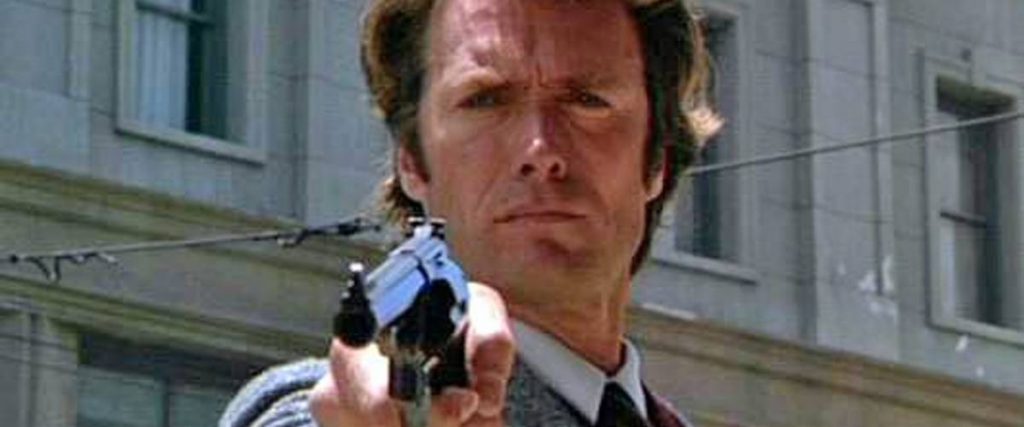

Take, as a brief example, his signature character of Dirty Harry. Harry Callahan is often a cold-blooded vigilante, frequently breaking the law to uphold it, who stubbornly denies the rights of criminals to protect the rights of victims. The dark complexity of the violence in those films caused several other A-listers to give it a hard pass, but it fit in perfectly with Eastwood’s revisionist persona of icons. His western heroes have sensitivity towards common everyman, but they are ruthless and cold-hearted towards the villains. This is never more deeply embodied than in his disturbing but powerful film High Plains Drifter, in which the very notion of justice as served by a devil is explored. Even in his lesser known mission/war films such as Kelly’s Heroes, Where Eagles Dare, or The Eiger Sanction, Eastwood is dealing with the stories of assassins, thieves, and deserters for whom the films frequently encourage us to root and cheer on.

There is not a single film in Eastwood’s first twenty that doesn’t contain at its core a complicated moral dilemma, most especially in the westerns and cop thrillers, and it’s much of what makes his work so interesting overall, even when the individual entries are sub-par.

The Ones You Shouldn’t Miss

The “man with no name” trilogy which launched Eastwood’s cinematic career is highly deserving of the attention it receives (with The Good, the Bad, & the Ugly getting the most recognition, although my personal favorite was For a Few Dollars More). But if someone wanted to separate out the best from the rest, here are my recommendations of the five films you should seek out to get a well-rounded picture of his early career:

For a Few Dollars More –

I’m likely to be court-martialed for this, but I still say this is a stronger film than The Good, the Bad, & the Ugly. The sheer scope and grandeur of GB&U give it tremendous credibility, but For a Few Dollars More is tighter, more suspenseful, and pushes nearly all of the same entertainment buttons (not to mention that it features the trilogy’s most compelling villain in Gian Maria Volonte’s volcanic performance). Ideally, the entire trilogy deserves to be seen, but all of the best elements of its power are on prime display in this middle chapter.

Kelly’s Heroes –

It’s far from essential. Heck, it’s barely important. But Eastwood’s early films are populated with either westerns, thrillers, or mission films, and the best of that third category in my opinion is Kelly’s Heroes. What primarily makes it work so well is the outstanding supporting cast (Donald Sutherland, Don Rickles, Telly Savalas, etc.). Eastwood himself is not even that prominent in the most memorable moments, but the overall impact of the film is fun and entertaining and if you want to experience some of the ensemble adventures that Eastwood chased after in a handful of these early films, give Kelly’s Heroes a look.

Play Misty for Me –

Clint Eastwood’s directorial debut is extremely impressive. It benefits from not being terribly ambitious, but it is still a tightly wound, deeply tense suspense thriller that maintains every inch of its power nearly fifty years later (thanks in large part to the phenomenal performance by Jessica Walter). I would recommend this film even apart from the interest in Eastwood’s filmography because it’s such a powerfully effective work of minimalist filmmaking. And I would, without qualification, consider it essential viewing for any fans of suspense thrillers. It’s great. Watch it.

Dirty Harry –

The original film that launched Eastwood’s most extensive franchise is unquestionably one of the most affecting films of his career. Directed by Eastwood friend and mentor Don Siegel, the film represents so much of the themes and characteristics of Eastwood’s appeal as a performer and persona. Harry Callahan remains one of the benchmarks for tough, take-no-crap heroism that culturally even rivals the strongest work of Willis, Stallone, and Norris. But what makes this first film so remarkable is the complexity of its theme and the vibrance of its style. Love it or hate it, it’s hard to deny the power and impact of Dirty Harry.

The Outlaw Josey Wales –

It lacks the brutality of nearly all of his other westerns. It lacks the propulsive pace of his thrillers and adventure films. But if you asked me to select just one film from Eastwood’s early years for you to watch, I would (with only brief hesitation) point you towards The Outlaw Josey Wales. At this stage in his career, Eastwood was more firmly developing his own distinct voice as a storyteller, and he had spent enough time in the genre to know where he could push the boundaries and where to hold the line. Although first-time viewers may find the episodic narrative challenging to navigate and the occasionally deliberate pacing difficult to maintain, chances are strong that the film’s more sensitive core will resonate long after the first viewing is completed. It is a film with as much heart as it has guts and a troubled soul anchored deep within its story that is nearly impossible to dismiss. And despite some stellar other entries, The Outlaw Josey Wales gets my vote for the best film of Eastwood’s first third.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.