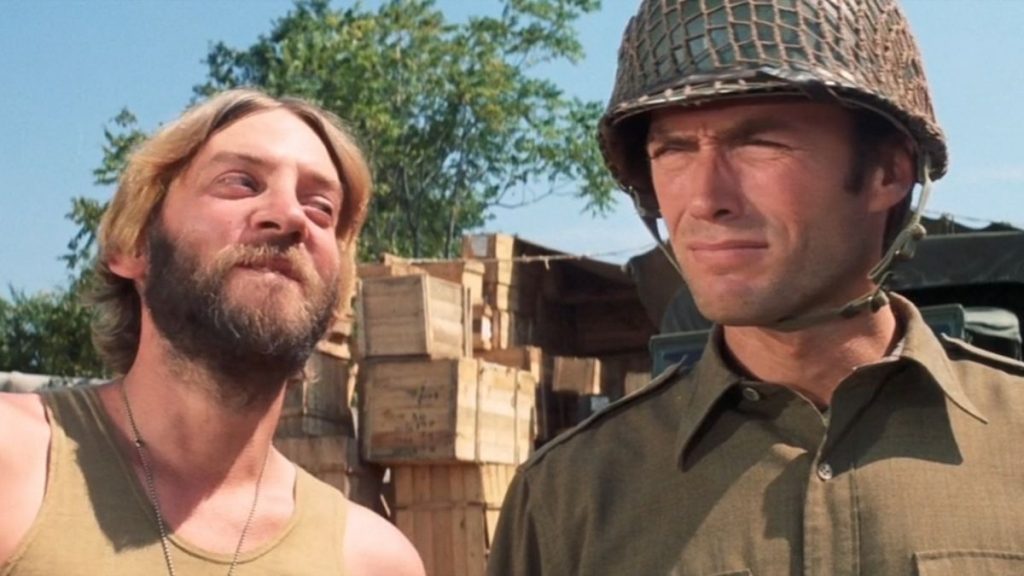

KELLY’S HEROES (1970)

“Sergeant, this bank’s not gonna fall into the hands of the American army. It’s gonna fall into our hands.” – Kelly

When Eastwood originally signed on to lead Kelly’s Heroes, he did so because it was supposed to be helmed by Don Siegel who, following Two Mules for Sister Sara, Eastwood considered his personal friend and favorite director. However, Siegel was bogged down with post-production on that film and unable to fit the production schedule. Meanwhile, Eastwood was unable to back out of his contractual obligation.

Directorial duties then fell to Brian G. Hutton, who had previously helmed Where Eagles Dare. In a few ways, Kelly’s Heroes is quite similar to that film. it features a troop of soldiers on a mission behind enemy lines, but unlike the weighty and twist-filled Where Eagles Dare, this mission is of a more personal nature and the tone is much more light-hearted and direct.

The 34th Infantry Division are disgruntled, frustrated, and overwrought. Their captain is glaringly selfish and whenever he decides to lead his men at all, he frequently positions them either in the way of harm or of boredom. When Private Kelly (Clint Eastwood) learns from a captured German officer about a bank filled with millions of dollars in gold bars, he resolves to travel behind enemy lines to break in and steal the loot. Enlisting the aid of his fellow disgruntled officers, along with a ragtag group of misfits from other divisions, the group cross into enemy territory and begin a series of adventures in misdirection in an effort to obtain the gold.

Eastwood carries top-billing this time, but he’s a bit dwarfed by the rest of the impressive cast. The cast includes the brutish and intimidating Telly Savalas, the apoplectic and hilariously obnoxious Don Rickles, and – in one of his most delightfully eccentric performances – the hippie-zen-warrior “Oddball” played by Donald Sutherland. The cast also includes Carol O’Connor as a naïve commander and Gavin Macleod as a perpetually furious army mechanic. Eastwood anchors the chaos with a steady and assured performance that is by no means a step backwards, but is hard to find impressive amidst such a colorful and entertaining collection of co-stars.

The film deftly balances some genuinely exciting action sequences with a constant thread of sardonic humor. But it is the most cynical film in Eastwood’s filmography thus far, often criticizing without any subtlety the hazards and pointlessness of wartime conditions. Not only is the mission at the plot’s base a mission of profit and desertion, but along the way, the “heroes” of the title enlist the help of nearly every disillusioned soldier, including at least one Nazi. The cynicism becomes perhaps most apparent when the soldiers – essentially on a bandit’s mission – are mistaken for bold and devoted patriots who are making an advance against the enemy (prompting the joke of the film’s title).

There is an utterly chilling moment when, following a particularly significant victory, a Nazi solider who has joined their treasure hunt instinctively gives the Nazi salute, momentarily stunning Private Kelly into remembering who they were before this mission. Once this shocking instinct is realized, the same Nazi alters his posture into a military salute, letting his mouth drift into a self-righteous smirk. It’s a provocative moment of glaring indictment against the whole enterprise that is unsettling and unforgettable.

But despite these alarmingly biting elements, this film manages to be highly entertaining and paced like a bullet, displaying once again Hutton’s talent for handling wartime mission narratives. It is often laugh-out-loud funny and occasionally poignant. It also contains possibly intentional echoes of Eastwood’s collaborations with Sergio Leone, most noticeable in a climactic scene where he, Savalas, and Sutherland face off against a Tiger Tank in a fashion unmistakably reminiscent of a western showdown. With strong characters, a simple and direct narrative, a steady pace, and a sharp tone, Kelly’s Heroes is an easily recommendable war film, whether you enter it with or without affection for that type of film.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.