ANY WHICH WAY YOU CAN (1980)

“Why me, Lord? You made other men out of clay. Mine, you made out of s$%#.” – Cholla, Black Widow Leader

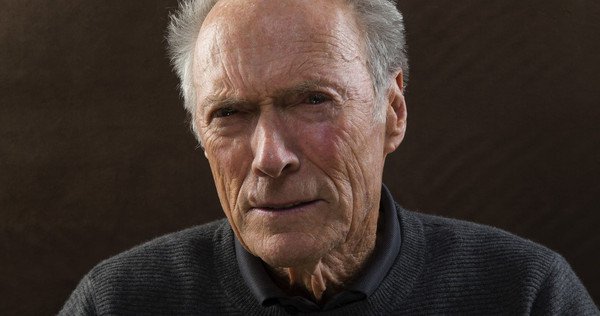

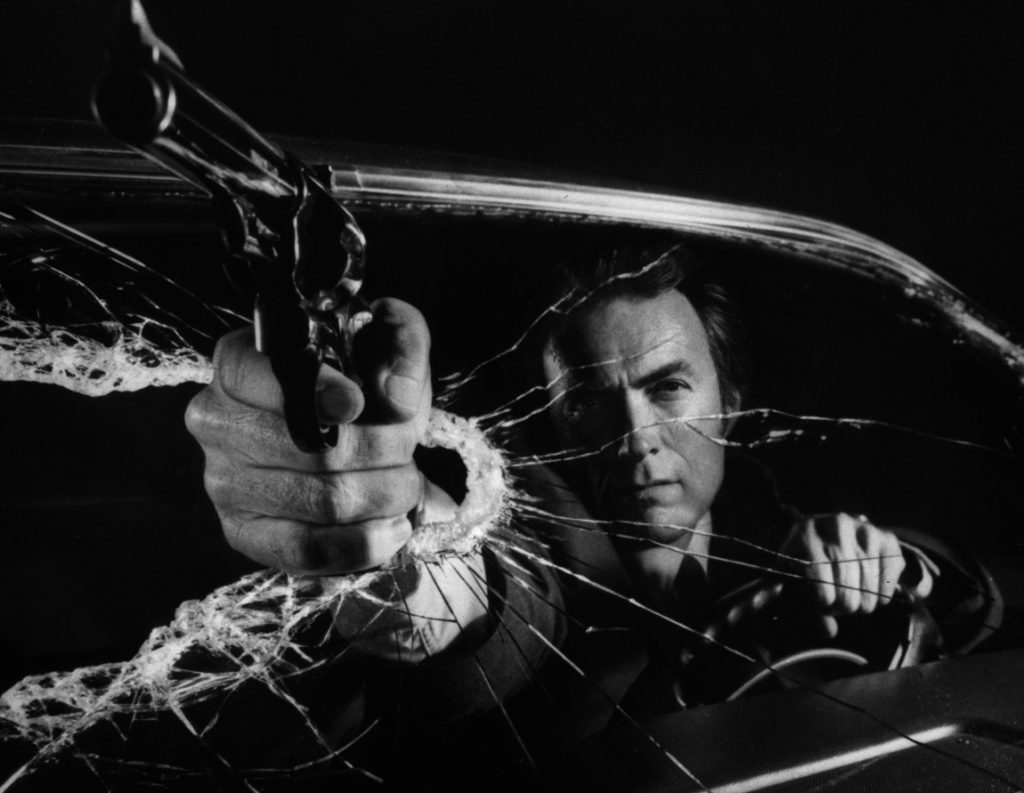

At this point in his career, only two of Clint Eastwood’s films had received direct sequels: A Fistful of Dollars and Dirty Harry. Both had come to help define his persona and cinematic footprint. But given the rabid financial success of Every Which Way But Loose, a sequel was not only understandable – it was inevitable.

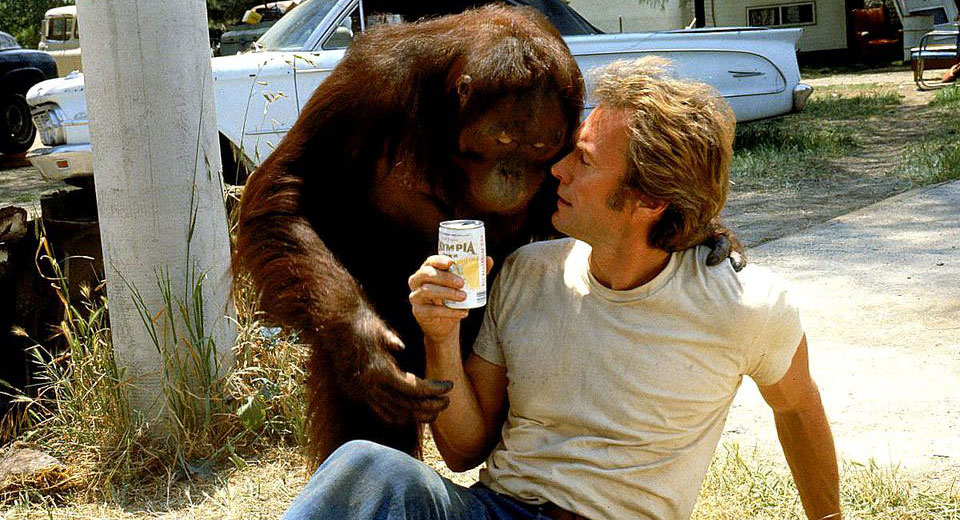

Any Which Way You Can follows a very similar formula to its earlier predecessor. Philo Beddoe (Eastwood) is still bare-knuckle brawling alongside his corner bookie, Orville (Geoffrey Lewis, reprising his role) and they’re both still side-stepping the bumbling and cantankerous Black Widow Gang. Along for the ride too is the faithful orangutan, Clyde and Orville’s ornery Ma (Ruth Gordon). Not to be left out, the pair also cross paths once again with Lynn Halsey-Taylor (Sondra Locke), who had left Philo broken-hearted and wounded-ego’d in the last film.

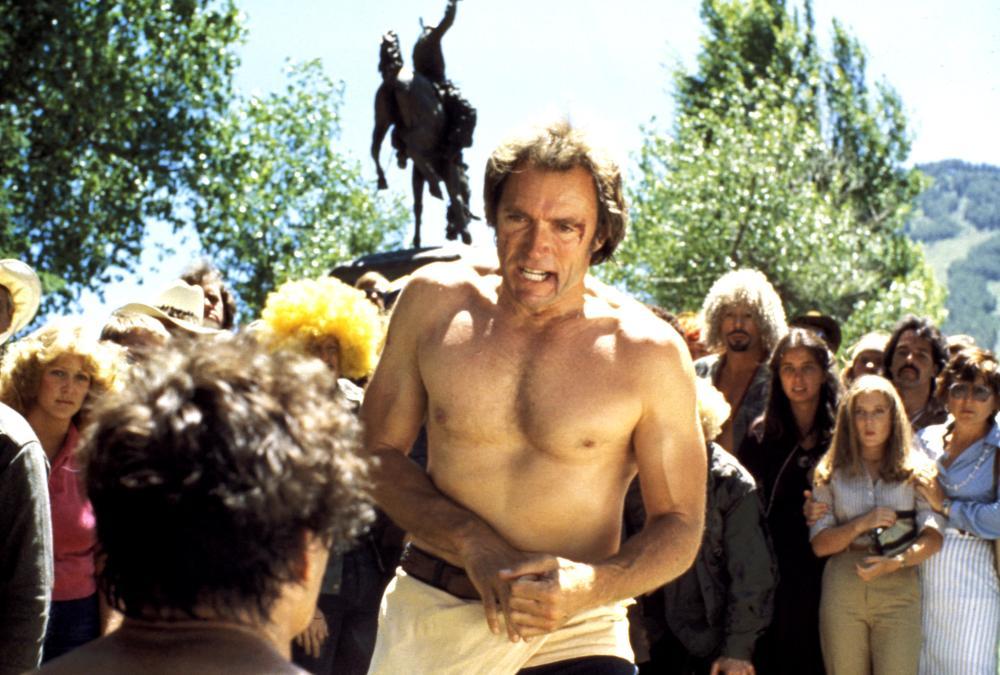

What’s different this time around is that Philo is genuinely wanting out of his brawling habits. He’s starting to become addicted to the pain and does not want to spend the rest of his days in a brawl with himself. He’s coaxed out of a self-imposed retirement by the representatives of the undefeated Jack Wilson (played by William Smith) who believe the underground fighting arena would pay huge sums to see the pair do battle. When Philo refuses, they kidnap Halsey-Taylor as leverage, which sparks a madcap series of chases in the film’s latter half as Orville and Philo pursue a rescue, the Black Widow Gang pursue revenge, and the bare-knuckle brawling bookies pursue a major payday.

Directed by long-time Eastwood stunt double, Buddy Van Horn (whose most prominent on-screen appearance had been in High Plains Drifter), Any Which Way You Can is, pound for pound, a funnier, faster, and generally more entertaining film than Every Which Way But Loose. Its elements are more absurd and less credible, but the laughs are sharper and the final fist-fight has more interesting stakes (not to mention a genuinely better matched opponent in Wilson). In purely objective terms, it’s a lesser film for all of its outrageousness; but it’s also a difficult film not to enjoy.

There isn’t much to credit in terms of performance that wasn’t there in the first film except that the leader of the Black Widow Gang (a buffoon named Cholla played by John Quade) is given a surprising glut of comedic opportunities. Quade was in the first film playing the same character, but that earlier film tried not to push the absurdity boundaries very much whereas this film embraces the looney tunes nature of the gang of knuckleheads. Cholla’s lines (as well as the overall narrative arc of the gang) are better in this film and the film is better for their continued presence.

Eastwood, Lewis, Gordon, and Locke are each as watchable and engaging as they were the first time around (if not more so). One element of this entry that I enjoyed tremendously was that the final fight sequence between Philo and Wilson is evenly matched and genuinely tense. Eastwood has had a multitude of fist-fights in nearly all of his films, and in almost every one of them he single-handedly mops the floor with his opponents. However, in the fight in this film, he’s not only evenly matched, there is a genuine question through out the whole fight as to whether or not he will win. I won’t spoil the outcome for you here, but there are some anxious surprises in the midst of it that I frankly found refreshing.

There is an element to the film which is worth noting, although it is sad and disturbing. There is an on-screen fight between a ferret (called a mongoose in the film) and a rattlesnake. The American Human Society gave a pass to the fight sequence (even though it looks uncomfortably realistic) because the rattler had been milked and defanged and therefore posed no real threat to the ferret. In my opinion, the fight looks too realistic to have been anything but traumatic for the animals whether or not they survived. However, the real tragedy of the film is that the orangutan who portrayed Clyde was beaten to death by his trainer shortly after filming wrapped (reportedly for stealing donuts from the set). It is tragic to think of the basic care and respect that was denied these animals on set and regardless of the justifications of a different sociological climate, it is upsetting to hear of such horrific behavior in an otherwise delightfully joyful and silly movie.

With the sincere asterisk pinging the treatment of the animals on set (which may understandably upset certain viewers beyond excuse), Any Which Way You Can is an otherwise fun, delightful and charming entry for Eastwood. If viewers were remotely a fan of Every Which Way But Loose, viewing this sequel is a no-brainer, but it’s even easy to recommend for the casual viewer looking to see a bit of Eastwood’s lighter side.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.