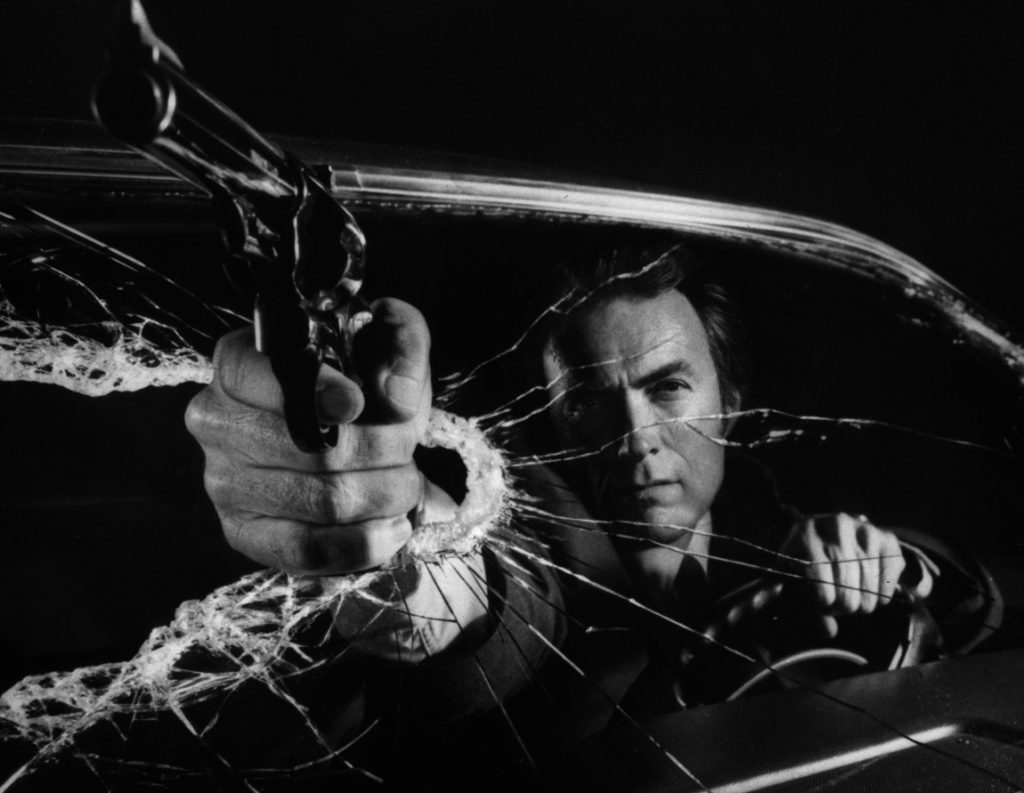

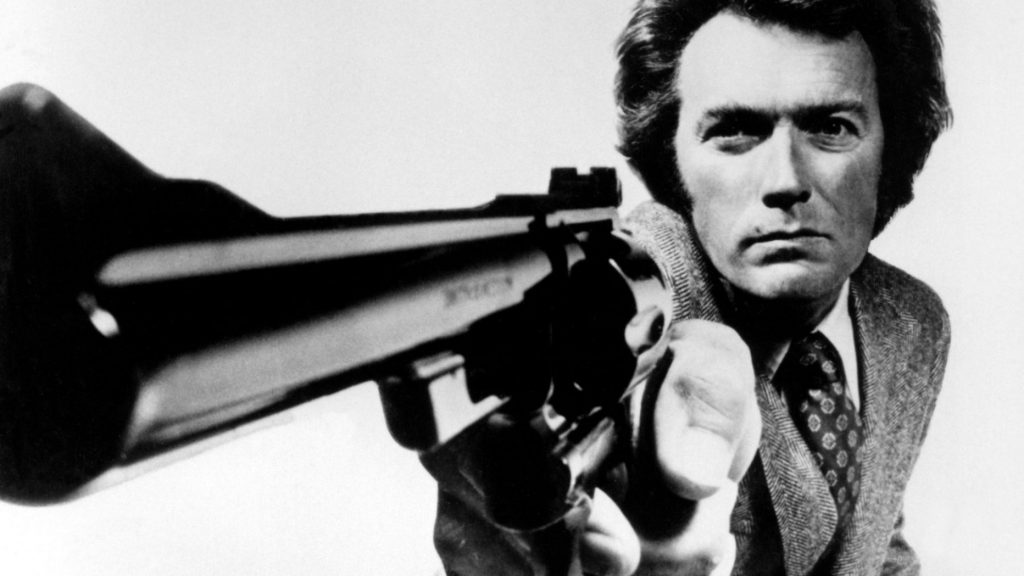

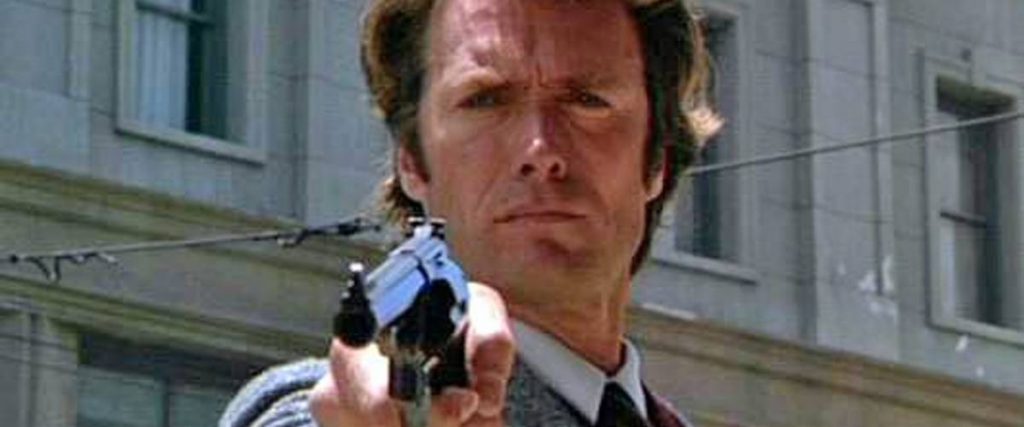

COOGAN’S BLUFF (1968)

“You better drop that blade, or you won’t believe what happens next, even while it’s happening.” – Coogan

Work began on Coogan’s Bluff (the second of three Eastwood films released in 1968) even before Hang ‘Em High had been released. The original script had appealed to him and offered a welcome chance to move away from the westerns for which he was known without really moving away from them. Essentially, the film is a western in tone, style, and characterization, but set in 1960s New York City.

The plot involves a womanizing and reckless Chief Deputy from Arizona named Walt Coogan (Eastwood, of course) who is given orders to extradite a prisoner he’d previously captured from New York City. While in the city, he finds himself in conflict with the bureaucracy standing between him and his prisoner and a stubborn Chief of Police (played by Lee J. Cobb). He bypasses the process with lies and exaggerations to get his hands on his prisoner, but he is then tricked and ambushed and the prisoner escapes. What follows is a vigilante manhunt through the city, against the will of both the city police and his own chief back in Arizona, wherein Coogan attempts to bring his escaped convict to justice.

The film was a decent hit in 1968, so I was excited to see it (it’s the first one in this year-long challenge that was new to me). It is most notable for being the first partnership between Clint Eastwood and Don Siegel (who would go on to direct Eastwood four more times, most notably in Dirty Harry). Prior to their pairing for this film, neither of the two men had even heard of each other, but they worked well together and became good friends off-set as well.

As for this first outing for them, Coogan’s Bluff is very “of its time”, which isn’t entirely a compliment. The sensibilities of late-60s/early-70s cop thrillers aren’t terribly appealing to me and some of them border on distasteful, particularly in their treatment of women (of which Coogan’s Bluff has a handful of transgressions). The script is often painfully utilitarian, the direction is straightforward and pedestrian, and the general resolution feels too tidy given some of the narrative’s general complications. In short, it’s easy to see why contemporary audiences enjoyed it, but it doesn’t hold up very well.

What works about it is Eastwood’s steady – if unremarkable – performance, two genuinely thrilling action sequences (one of them a motorcycle chase and the other an out all brawl in a pool room), and an even, simplistic narrative. Unfortunately, these merits don’t quite elevate the material beyond the status of a Saturday afternoon cable matinee. It’s worth noting that the script was a matter of some frustration for Eastwood. He had originally been drawn to the simplicity of the original script, penned by Rawhide veterans Herman Miller and Jack Laird as a possible TV pilot. But upon hiring writers to make the script more cinematic (and watching it go through several unlikable drafts), Eastwood rejected any further rewrites in favor of going back to the original concept. Dean Reisner was finally hired and, with considerable input from Eastwood himself, a new script was finished. This overall experience would start a long-standing distaste in Eastwood’s work for extensive revisions to scripts.

I can’t speak to the quality of the scripts that didn’t make it to the screen, but the one we finally get isn’t very good. It isn’t surprising that it was originally conceived as a TV pilot (the overall production has a decisively small-screen feel), but the script has three major problems:

First, the character of Coogan isn’t very likable (or effective). His treatment of women seems inconsistent (he slaps a man for groping a woman without permission, but frequently makes unwanted advances himself and even roughs up a woman late in the film to obtain information). It’s also his own impatience which causes the primary problem in the first place. His “bluff” subverts due process and enables the prisoner to escape. It’s difficult to root for a hero so fundamentally impetuous and arrogant. Eastwood plays Coogan with an appropriate blend of machismo confidence and gruff rebellion. It’s a steady and assured performance, but ultimately unremarkable and made even less so by how unlikable the character is.

Second, the film’s treatment of women is – at times – painfully offensive. In the character of Julie Roth (played by Susan Clark), the film seems to be attempting to present an independent and self-sufficient working woman, but her inevitable swooning over Coogan and her passivity towards moments of objectification are troubling at best and offensive at worse. All other female characters are reduced to objects of either Coogan’s affections or the villain’s (including the one Coogan eventually starts tossing around a room). It may not be uncommon given the times in which the film was made, but it’s uncomfortable and potentially upsetting to current sensibilities.

Lastly, the stakes in the script are simply too small. The reason for Coogan’s inability to extradite the prisoner is described in only the broadest of terms (which might support the character’s reason for bypassing it entirely). But even after Coogan’s “bluff” to get his hands on the prisoner lands him in deep trouble with both the local and his own direct authorities, his continued vigilante tactics are eventually dismissed with impunity simply because they are ultimately successful (yes, I know I just spoiled the ending of the film, but with a film like this you’ll already see the ending coming from an hour away).

Coogan’s Bluff is, in many ways, a very natural next step in Eastwood’s filmography. Coogan wears a cowboy hat (and is often referred to as “cowboy” by other characters). He carries himself very much the way Jed Cooper from Hang ‘Em High carried himself, with simple drives and simple goals. He’s the same basic character we’ve already come to know him as playing, just in the city instead of the west. Fans of this genre’s period will likely find this to be a perfectly acceptable entry, if not an impressive one. But for the casual film viewer, Coogan’s Bluff is little more than mild, diversionary fare.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast,

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast,

Aaron White is a Seattle-based film critic and co-creator/co-host of the Feelin’ Film Podcast. He is also a member of the

Aaron White is a Seattle-based film critic and co-creator/co-host of the Feelin’ Film Podcast. He is also a member of the