A FISTFUL OF DOLLARS (1964)

“Get three coffins ready.” – Joe

In 1964, legendary Italian director Sergio Leone changed the Western genre of cinema forever.

Prior to that time, westerns (which had been an exclusively American film genre) had been established and populated by tales of cowboys and outlaws, good guys who wear white and bad guys who wear black, wagon trails and cattle drives, not to mention a genuinely regrettable trend of negative portrayals of Native Americans and their culture. Pioneers of the genre, most notably John Ford, had carried the tropes and patterns about as far as they could go under the original paradigm. Most of them did not deal with morally complex heroes (with a few notable exceptions like The Searchers or The Treasure of Sierra Madre). And while those foundational elements are irrefutably brilliant, the genre’s popularity and effectiveness had waned by the mid-60s.

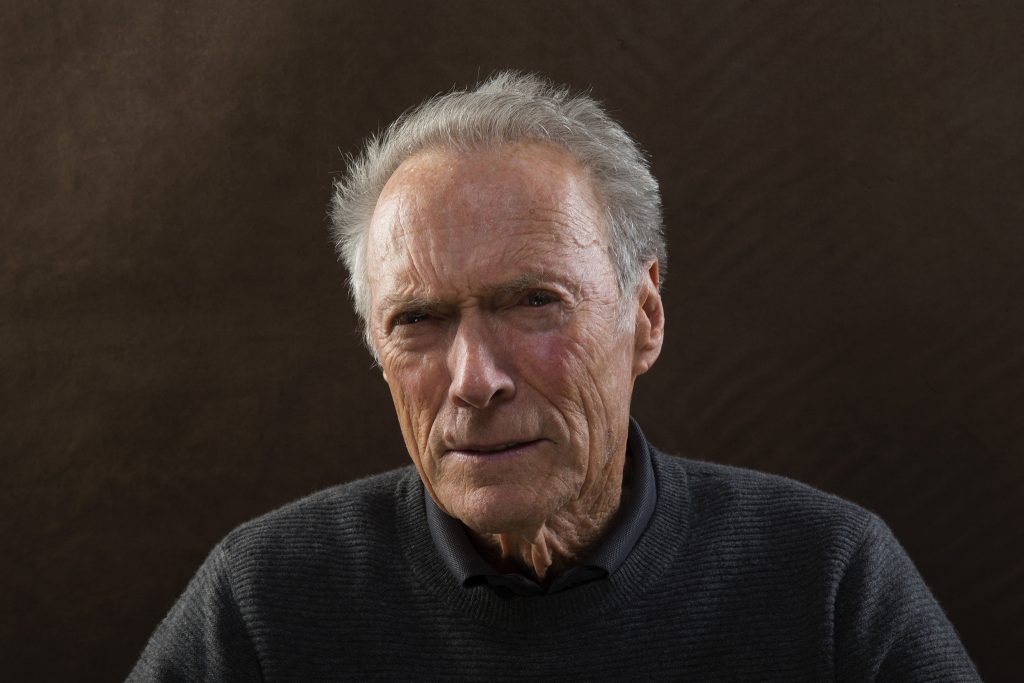

Enter Leone. Leaning on the plot of a recent Japanese film by Akira Kurasawa called Yojimbo (a stunt which got Leone successfully sued by Kurasawa’s production studio), and wanting to reinvigorate and revitalize the western genre, Leone envisioned a battle-weary town torn and terrified by the clashes of two rival families into which — one day — a stranger would ride and ignite the end of the longstanding feud. That stranger? None other than Clint Eastwood, taking on his first starring film role in the first installment of a trilogy that would propel and largely define his stardom.

There is a mountain of things to say about A Fistful of Dollars as a film and how it virtually redefined the western genre in ways which remain standard. It increased the violence and darkened the tone. It sharpened the landscape and sullied up the wardrobes. It presented a notably more brutal and unflinching world in which its characters would inhabit.

But most of all, it fashioned at its center a hero whose motives are foggy and whose morals are even murkier. He is compassionate towards and even rescues a poor family from devastation at the hands of the murderous family, but has no qualms or reservations about lying, scheming, and even casually leveraging dead bodies for his own financial gain. When the film begins, he appears to be merely a bounty hunter and enterprising gunslinger, but as the narrative progresses his deeper intentions (which border on the anarchic) emerge.

The film was, at the time, the most successful Italian film in history, spawning two even more successful (and most agree objectively better) films comprising a thematic and stylistic trilogy. When all three films came to the states (they’re called spaghetti westerns solely because they were made by an Italian director) they achieved identical success and skyrocketed the fame and career of Clint Eastwood.

Eastwood, for his part, delivers an assured and compelling performance in his first turn as “The Man with No Name.” He had played numerous supporting roles at this point in his career and had even been the steady leading role on nearly eight seasons of Rawhide for television. But his character here (occasionally called and credited as “Joe”, which is never confirmed) is firmly an antihero, the reverse in many ways of the white-hatted hero of previous landmark westerns.

What Eastwood brings to the role is a decisively enigmatic quality. His handsome face and humor-flavored voice contrast a distinctly menacing undertone. And when he squints — an entirely practical affectation caused by too much glaring light in his face — he puts on the facade of a mythic warrior, as intimidating as he is controlled. Leone (who originally did not want to cast Eastwood) later praised the subtlety of the performance, referring to it as appropriately binary. Leone is quoted as saying, “Eastwood, at that time, only had two expressions: with hat and no hat.” It echoes the ancient comedy and tragedy masks of classical Greek theater.

While the range is certainly limited at this point, it already foreshadows a depth and complexity Eastwood would later explore both in front of and behind the camera. For now, he shows up, makes his move, and then drifts off into the sunset. It’s an epic beginning to an epic career.

Richard Harrison, the popular western star who Leone wanted to cast (after Henry Fonda, Charles Bronson, and a slew of others turned him down) first recommended Eastwood for the role. Harrison would later state, “Maybe my greatest contribution to cinema was not doing A Fistful of Dollars and recommending Clint for the part.”

Honestly, with all due respect to Harrison’s fine work, I can’t say I disagree.

P.S. Although this series focuses primarily on Clint Eastwood’s evolution as an actor and director, it’s impossible to discuss A Fistful of Dollars without mentioning the iconic score of Ennio Morricone, who crafted an indelible soundscape into which westerns would venture for decades to follow. Simultaneously intimate and grand, Morricone’s score is as credited for the success of A Fistful of Dollars as either Eastwood or Leone. It’s a brilliant work and deserves its place in cultural legend.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

DON SHANAHAN is a Chicago-based film critic writing on his website

DON SHANAHAN is a Chicago-based film critic writing on his website