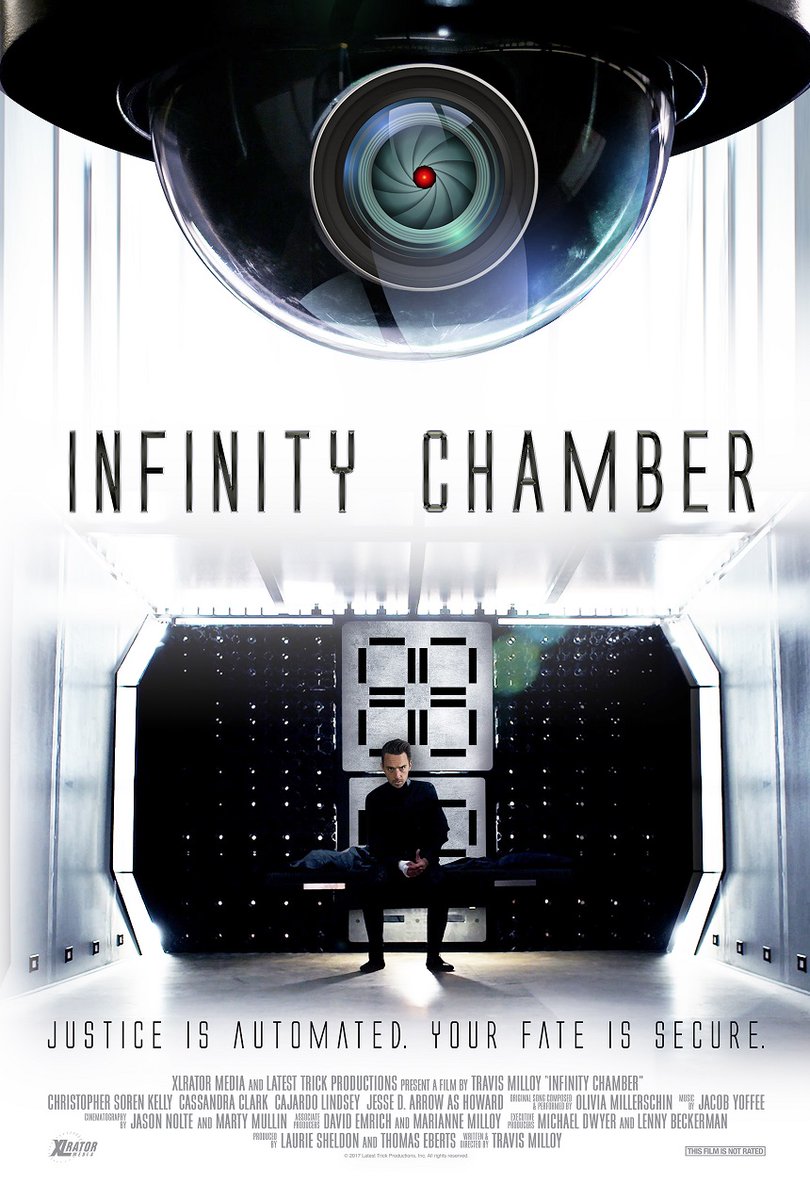

Infinity Chamber (2017)

Going In

A man trapped in an automated prison must outsmart a computer in order to escape and try and find his way back to the outside world that may already be wiped out.

Rarely does a cerebral science fiction film slip beneath my radar. I have a deep love of contemplating the complexities of life, human emotion, and decision making while exploring realistic future technologies. So when I learned of Infinity Chamber’s existence AFTER its release straight to VOD, I was a bit surprised. Granted, this is not a big studio picture with A-list actors. Formerly titled Somnio during a failed Kickstarter campaign, it is written and directed by Travis Milloy, who previously penned 2009’s space horror Pandorum (which I quite enjoy). Knowing that, and coupled with the incredibly intriguing synopsis above, I couldn’t miss seeing this one at the first opportunity.

COMING OUT

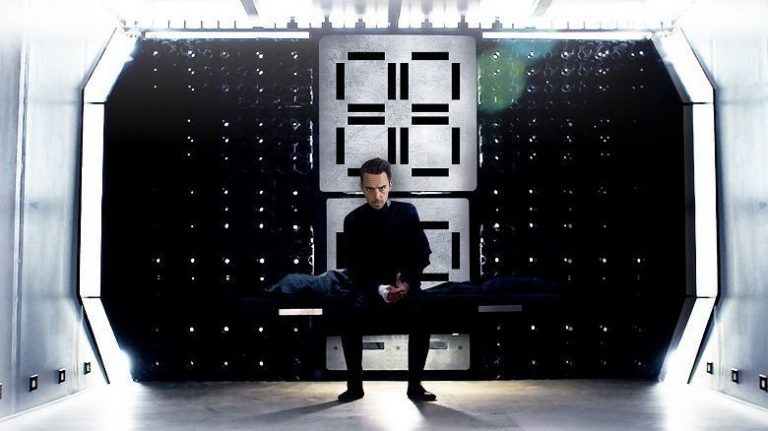

Imagine, if you will, that you wake up with a massive headache and a foggy memory. Before you is a talking eyeball who introduces himself as “Howard”, informs you that you are not being charged with a crime, but rather being “processed”, and says that his job is to keep you alive.

I don’t know about you, but that would definitely give me cause for concern, and Frank Learner is no different. This interaction sets forth in motion a very slow-burn, thought-provoking story. For those that have seen Duncan Jones’ fantastic film Moon, its inspiration is unmistakable. That’s not to say that Infinity Chamber can’t stand on its own. It can. But the feel is similar, so using that as a reference point may help in determining whether this is your kind of flick.

As the plot unfolds, Frank (Christopher Soren Kelly) tries to figure things out, all while working towards a solution for release… or escape. Kelly’s performance is very good and requires quite a bit of silent acting. Due to the film mostly taking place in a single location and clearly made on a very low budget, the heavy lifting falls on his ability to both physically and emotionally carry each scene. Other human actor performances are good, as well, but most of the movie is Frank interacting with “Howard,” and this is where the film doesn’t win me over quite as much.

In movies like Moon and 2001: A Space Odyssey, the artificial intelligence is as much a character (thoroughly developed) as the human actors, and I just didn’t get that feeling from “Howard.” Not that the voice work is particularly bad, it just wasn’t anything… special. I did not develop empathy or understanding in the way that I did for HAL or GERTY in the aforementioned films. Unfortunately, that was a detractor for me since the A.I. is one of the two main characters. My other complaints are mostly minor, with the other primary one being that some scenes became repetitive and added too much time to the film. The nature of the film almost demanded that we have these scenes, and it’s a fine line to balance, but the result was that the movie loses its thriller label midway through before picking it back up in the third act.

Verdict

Infinity Chamber is a smart, well-acted, and creative story that deals with themes of isolation and identity in interesting ways. Even “Howard” wrestles with what he is and can be, providing a fresh take on the evil A.I. trope. The film tackles questions about our relationship with technology that will give fans of this genre a lot to talk about with others who’ve seen it. As of this writing the film is available to rent on Amazon and iTunes and is definitely worth a watch.

Rating:

Aaron White is a Seattle-based film critic and co-creator/co-host of the Feelin’ Film Podcast. He is also a member of the Seattle Film Critics Society. He writes reviews with a focus on how his expectations influenced his experience. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter to be notified when new content is posted.

Aaron White is a Seattle-based film critic and co-creator/co-host of the Feelin’ Film Podcast. He is also a member of the Seattle Film Critics Society. He writes reviews with a focus on how his expectations influenced his experience. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter to be notified when new content is posted.