Last year, I spent time watching the films of Alfred Hitchcock. I watched them in chronological order of their release, from the first to the last.

The experience was revelatory in a number of ways. Certain thematic and narrative patterns emerged that would have otherwise remained buried in the bubble of the individual films. When taken in sequence, certain anomalies become fascinating sources of consideration for what might be happening in the life or career of an artist to draw them towards a particular project, even if something is done merely for the paycheck.

I love viewing such patterns and trends in the work of an artist. But when their films are viewed out of sequence to when they were made, it’s much more difficult to ascertain the shape and evolution of those patterns. You have to see what they did at point D to understand why point F looks and feels the way it does.

Artists – good ones anyway, but especially great ones – change as time carries on. The changes may be subtle, and perhaps not for the better, but the change is inevitable. And most of all, the change is interesting. Because an artist may be either embracing or rejecting certain notions about their own craft and legacy in real time according to the pieces they produce. Observing that linear evolution helps us to understand why they’re revered as artists, what the most common elements of their contribution to the art form are, and in many ways helps us to better understand why their material resonates (or doesn’t) with the larger artistic community.

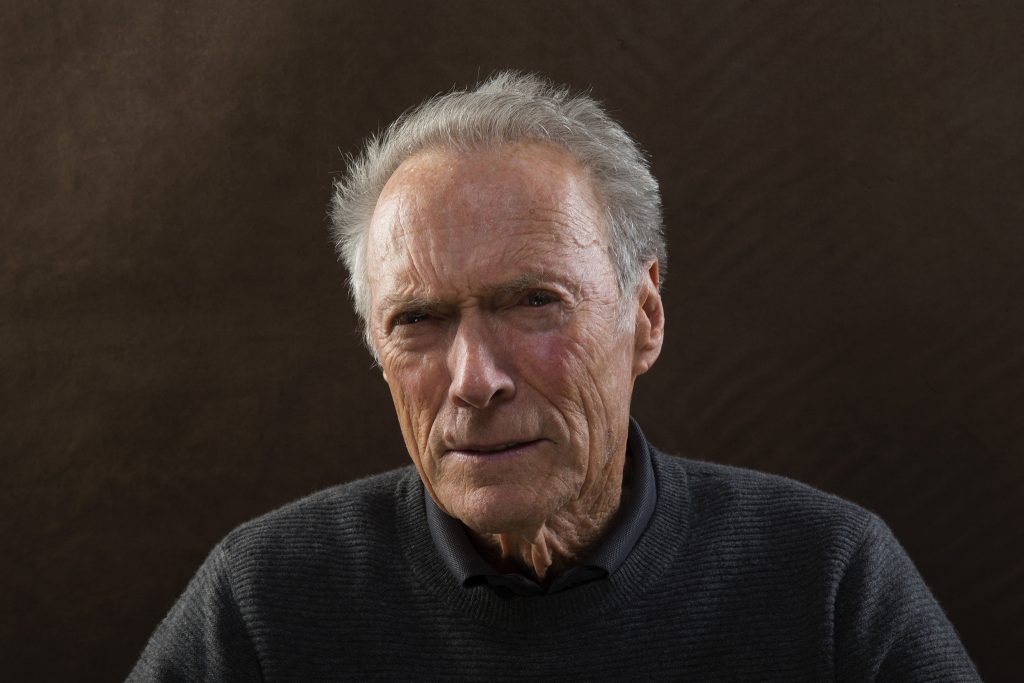

For this year, at Feelin’ Film’s request, I’ll be turning my attention towards the work of Actor, Producer, Composer, and Director Clint Eastwood.

Eastwood emerged in the 50s and 60s as a man straight out of the western fabric of John Ford’s landscape: a strong, silent type who let his guns and his fists do most of his talking as the occasion called for it. But unlike the legends of the cinema who populated those early works (like Wayne, Cooper, Peck, and Stewart), Eastwood was darker, with an undercurrent of malice and spite. His ethics were more complicated and his characters were frequently more brutal.

Eastwood eventually solidified himself as somewhat of a mythic figure on the American cinematic landscape. Whether embodying drill sergeants, gunfighters, or the play-by-his-own-rules-of-justice lawman Dirty Harry, Eastwood became a quintessential symbol for the righteous outlaw. A take-no-guff, independent, machismo hero.

Yet, many of his films (specifically those which he directed) display a striking vulnerability and often a futility to their goals and aspirations. Frequently the victories come at irreversible cost, when they come at all. His career unveils some of the best and worst characteristics in our heroes, both the epic and the everyday variety.

So, throughout 2018, I’ll be charting his progress and evolution as an artist, both as an actor and performer (in primarily starring roles) and as a director. It’ll be a (hopefully) fascinating journey through the last 50 years of American cinema, through the lens of one of its most noteworthy icons.

The 60 films I’ll be covering are listed below, starting with Sergio Leone’s “Man With No Name” Trilogy and concluding with Eastwood’s planned 2018 release, The 15:17 to Paris.

Wish me luck… punk. I’m gonna need it.

Eastwood Films

| A Fistful of Dollars (1964 – Actor) | The Gauntlet (1977 – Actor/Director) | The Bridges of Madison County (1995 – Actor/Director) |

| For a Few Dollars More (1965 – Actor) | Every Which Way But Loose (1978 – Actor) | Absolute Power (1997 – Actor/Director) |

| The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966 – Actor) | Escape from Alcatraz (1979 – Actor) | Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997 – Director) |

| Hang ‘Em High (1968 – Actor) | Bronco Billy (1980 – Actor/Director) | True Crime (1999 – Actor/Director) |

| Coogan’s Bluff (1968 – Actor) | Any Which Way You Can (1980 – Actor) | Space Cowboys (2000 – Actor/Director) |

| Where Eagles Dare (1968 – Actor) | Firefox (1982 – Actor/Director) | Blood Work (2002 – Actor/Director) |

| Paint Your Wagon (1969 – Actor) | Honkytonk Man (1982 – Actor/Director) | Mystic River (2003 – Director) |

| Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970 – Actor) | Sudden Impact (1983 – Actor/Director) | Million Dollar Baby (2004 – Actor/Director) |

| Kelly’s Heroes (1970 – Actor) | Tightrope (1984 – Actor) | Flags of Our Fathers (2006 – Director) |

| The Beguiled (1971 – Actor) | City Heat (1984 – Actor) | Letters from Iwo Jima (2006 – Director) |

| Play Misty for Me (1971 – Actor/Director) | Pale Rider (1985 – Actor/Director) | Changeling (2008 – Director) |

| Dirty Harry (1971 – Actor) | Heartbreak Ridge (1986 – Actor/Director) | Gran Torino (2008 – Actor/Director) |

| Joe Kidd (1972 – Actor) | The Dead Pool (1988 – Actor) | Invictus (2009 – Director) |

| High Plains Drifter (1973 – Actor/Director) | Bird (1988 – Director) | Hereafter (2010 – Director) |

| Breezy (1973 – Director) | Pink Cadillac (1989 – Actor) | Edgar (2011 – Director) |

| Magnum Force (1973 – Actor) | White Hunter Black Heart (1990 – Actor/Director) | Trouble with the Curve (2012 – Actor) |

| Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974 – Actor) | The Rookie (1990 – Actor/Director) | Jersey Boys (2014 – Director) |

| The Eiger Sanction (1975 – Actor/Director) | Unforgiven (1992 – Actor/Director) | American Sniper (2014 – Director) |

| The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976 – Actor/Director) | In the Line of Fire (1993 – Actor) | Sully (2016 – Director) |

| The Enforcer (1976 – Actor) | A Perfect World (1993 – Actor/Director) | The 15:17 to Paris (2018 – Director) |

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.