THE GAUNTLET (1977)

“I’m warning ya, you mess around and I’ll put the cuffs on you. You talk dirty, I gag ya, if you run, I’ll shoot you. My name is Shockley, and we’ve got a plane to catch. Let’s go.” – Ben Shockley

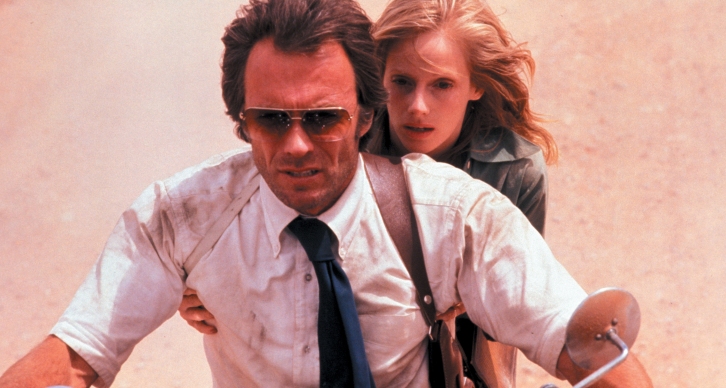

The script for The Gauntlet had been bouncing around development for a while before it landed with Eastwood. Previously attached stars included Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen, and even Barbara Streisand. When Eastwood eventually signed on to direct, he cast himself alongside his then real-life romantic partner Sondra Locke (who had first appeared with Eastwood in The Outlaw Josey Wales).

The narrative is, in many ways, reminiscent of Eastwood’s much earlier film Coogan’s Bluff. In fact, several comparative narrative beats made me wonder if there wasn’t a subconscious desire on Eastwood’s part to try that basic story again, this time helming the directorial duties himself. The premise is that drunk and disillusioned officer Ben Shockley (Eastwood) is sent on assignment to extradite a witness named “Gus” Malley for a “nothing trial”. Upon arrival, Shockley quickly realizes that someone powerful would do anything to make sure that neither he nor Malley makes it back to Phoenix alive, and the pair of them must navigate a treacherous series of ambushes, traps, and unfortunate encounters before eventually facing down a multi-block, heavily armed barricade.

The two films are similar in their basic extradition plotline and in the narrative elements of the protagonist stepping into trouble beyond his original understanding. But there are some major differences between The Gauntlet and Coogan’s Bluff that make The Gauntlet the unquestionably stronger film.

First and foremost is the presence of Locke as the feisty and resourceful Malley. Locke wasn’t given much to do acting-wise in The Outlaw Josey Wales except for pine, swoon, and worry (all of which she still managed to make believable). With the character of Malley, she is given a much richer character and she attacks the role with commitment and complexity. She steals nearly every scene she’s in (which is most of the movie) and the real-life chemistry between her and Eastwood make their dynamic on screen frequently crackle.

The script is also tighter and more direct, with a more logical and focused direction to its narrative. There are some obvious contrivances and conveniences, a handful of which may very well elicit eye rolls, but the general structure is noticeably stronger than Coogan’s Bluff. However, the script could have done more with its character development and presented a less outlandish resolution to the central conflict. When viewed in reference to the similarly-premised earlier film, the script shines. But taken as an isolated piece, it’s pretty pedestrian.

Eastwood himself is as reliable as always, boosted substantially by getting to work with Locke. As an actor, there isn’t much surprise here, but as a director it’s both a step forward and backward. It lacks nearly all of the rich thematic exploration of The Outlaw Josey Wales, which makes it feel somewhat regressive – I forgot several times in the viewing of it that Eastwood directed it. However, as an action thriller, Eastwood deftly navigates some authentically thrilling sequences. His experiences on The Eiger Sanction were more ambitious (and dangerous), but his instincts for pacing the thrills take a big step forward here. Nearly a fifth of the film’s budget was spent solely on the action effects and that investment shows on-screen.

All of this adds up to something of a mixed bag. The script is mostly innocuous (not to mention frequently trite and unbelievable), but the action sequences are genuinely exciting (particularly the bombardment of its outrageous climactic journey through the gun-saturated city streets) and Sondra Locke delivers a compelling and interesting performance. Fans of Eastwood’s more rough-and-tumble thrillers will find a lot to enjoy, but those looking for something with more depth or substance might be left shrugging it off.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.