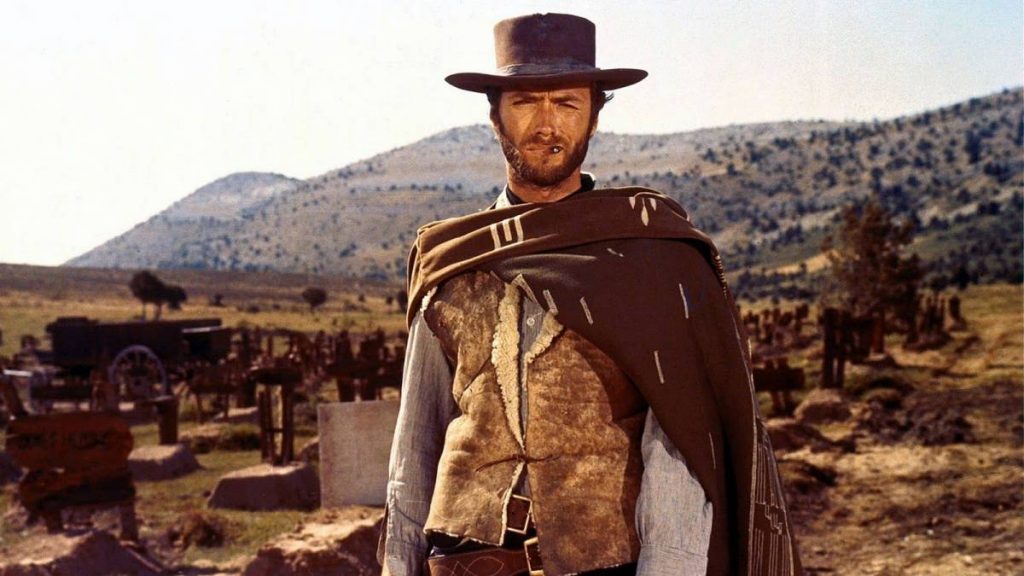

THE GOOD, THE BAD & THE UGLY (1966)

“I’ve never seen so many men wasted so badly.” – Blondie

I should get this out of the way right up front: I’m one of the very rare breed of film lovers who enjoys watching For a Few Dollars More more than The Good, the Bad & the Ugly. However, I do consider this third installment in the “man with no name” trilogy to be the more cinematically important film of those two, I think objectively that For a Few Dollars More is more tightly constructed and more focused overall.

This perspective was largely birthed out of this chronological, close-proximity viewing sequence. I watched each film with only a day’s break in between to collect and assess my thoughts on them. A Fistful of Dollars is a thrilling initial entry. For a Few Dollars More expands the world and enriches the character motivations substantially. The Good, the Bad & the Ugly attempts to do the same thing, while also making a handful of profound statements about the futility of violence and the cold reality of death. However, this third film takes so much time setting up that it feels unfocused in places.

There is undeniably cinematic greatness in The Good, the Bad & the Ugly. The simple narrative of three competing bandits in search of a buried treasure amidst the American Civil War has the advantage of being simultaneously intimate and epic. There are moments of tremendous emotional impact, such as the scene where Eastwood’s drifter gives his coat and hits of his cigar to a dying young soldier or the juxtaposition of the hauntingly beautiful song the soldiers sing as Tuco is beaten for information. The themes are provocative, as the violence is amplified and the body count is significantly higher (of course due to wartime casualties). The film was initially heavily criticized for its violence, but reassessment over time has redeemed and highly praised Leone’s vision.

If the films latter half were the bulk of the movie, with the first half trimmed down significantly, this would easily be my favorite in the series. There are moments in that latter half that are utterly unforgettable and vastly outrank any individual moment in the first two installments. However, the first half spends a lot of time establishing the scenario: showing us Tuco and Blondie’s tenuous partnership and the ruthless, homicidal glee that Angel Eyes exhibits. We are nearly an hour into the film before we fully know the primary search the three titular icons will undertake, and while in other films that would be no complaint, Leone takes too much time in my opinion getting to where we need to get for the necessary collisions. The pacing feels ambling, as if the film were finding itself out as it went along. But once Tuco and Blondie finally set out for the buried gold, things quickly and powerfully ramp up.

My other major complaint is the disparity between how much characterization is given to Tuco (about whom we discover almost everything) versus Angel Eyes and Blondie (about whom we see primarily motivations only). If the same sparse background were given to all three characters, things wouldn’t feel so off balance. As it is, the climactic battle feels inevitable in its outcome and much of the suspense is diluted, despite the powerful cinematography, performances, and musical score.

Eastwood is given less to work with in this film than in either of the two previous installments. In A Fistful of Dollars, he had to balance pitting two rival families against each other and revealing a subtle benevolence towards a couple of their victims. In For a Few Dollars More, he juggled distrust and admiration for his new companion without ever losing the malice and threat towards the hunted bandits. But in The Good, the Bad & the Ugly, he merely has to appear, look stoic and melancholy, and squint as frequently as possible. I’m not criticizing the performance, but the weight of interesting narrative beats are nearly all shifted to Tuco’s character (played by Eli Wallach). Just as For a Few Dollars More was mostly Colonel Mortimer’s story, The Good, the Bad & the Ugly is mostly Tuco’s, but unlike that previous film, Leone gives Eastwood’s bounty hunter less to work with, not more.

Eastwood still delivers a compelling performance simply by standing up. It’s worth noting that this film is technically a prequel to the first two, with Eastwood not obtaining his trademark poncho until late in the film (following arguably the film’s most powerful moment). Eastwood is captivating and charismatic, but he appears to be on autopilot for a large section of the story. Perhaps his working relationship with Leone was growing tiresome (they never worked together again) or perhaps he was ready to move on to other roles, but he does seem a bit more distant in this narrative than in the first two stories.

This film is nearly universally praised. Perhaps my disappointment in this viewing is more grounded in a reaction to that praise than to the film itself. Because it is undeniably an epic achievement, deeply influential in both cinematic style and the boundaries of film at large. If my review sounds like a non-recommendation, please don’t take it as such. This is a film that deserves to be seen and that you will likely highly enjoy.

But, in charting the “Evolution of Eastwood”, the film takes a surprising (if notably tiny) step backwards. Maybe this provides an explanation for why he wouldn’t appear as “the man with no name” again, at least not for Sergio Leone.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.