HIGH PLAINS DRIFTER (1973)

“It’s what people know about themselves inside that makes them afraid.” – The Stranger

It’s highly appropriate – almost poetic – that Eastwood’s second directorial feature would be a western. What is even more bold and provocative is for it to have been High Plains Drifter, a brutally bleak and gritty story that is grim, violent, offensive, and – perhaps literally – haunted. It’s also deeply compelling and remarkably effective.

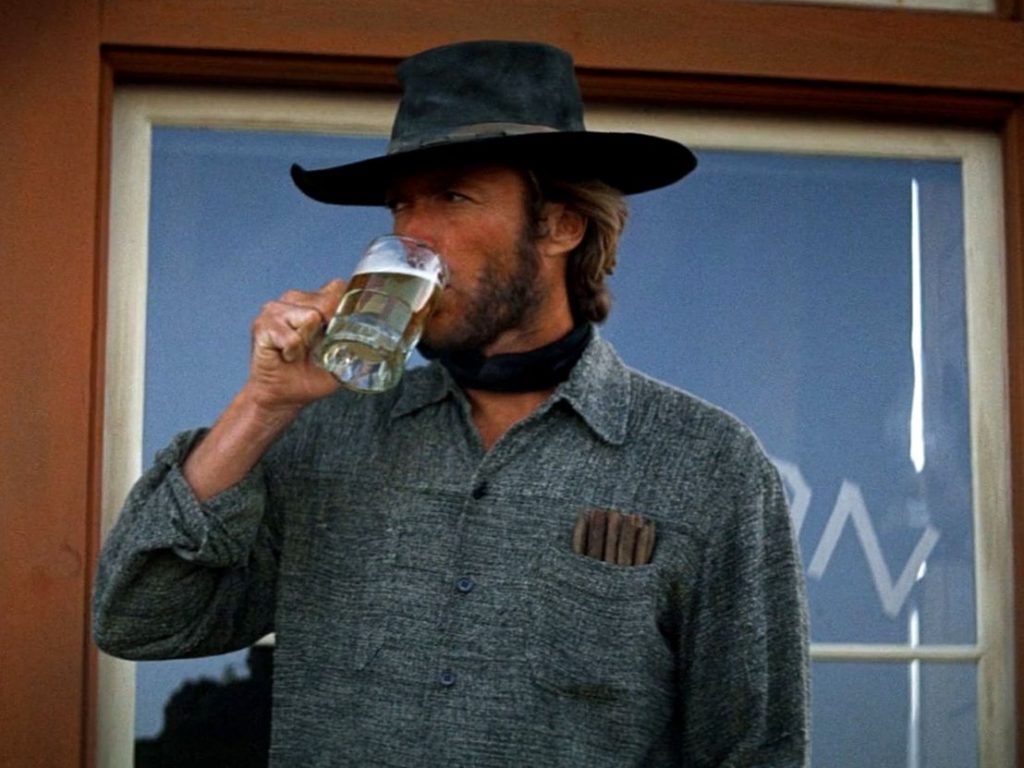

The film opens with a horizon shrouded in a blurry heat. Suddenly, not so much emerging as fading into view, a single rider makes his way into the town of Lago, with every public townsperson standing in suspicious awe as he rides through. Within minutes of his arrival, he has killed three men and raped a woman in broad daylight. The next day, this same stranger is commissioned out of desperation to protect the town from the impending threat of three former residents who will soon be released from prison and make their way back to town to enact revenge on those who imprisoned them. He accepts the offer and begins to make every use of his newfound power, rattling every complacent and corrupt citizen’s routine existence into chaos. By the time the three villains do arrive, a deeper and darker purpose behind the stranger’s presence in the town begins to fully reveal itself.

Eastwood returns to his old familiar character, this time a literal “man with no name” as his identity in the film is never confirmed (his character is even credited as “The Stranger”). His performance here is as volcanic as it has ever been, and it is surrounded by a host of equally compelling performances under Eastwood’s strikingly assured directorial hand. The script was fashioned by Oscar-winning screenwriter Ernest Tidymen from a 9-page treatment pitch. It is saturated in mystery and soaked in dread: a quality mirrored in the film’s shadowy visual aesthetic and ethereal musical score. Indeed, the overall tone of the film and the feelings behind some of its individual moments are far more akin to ghost stories than to western legends.

It is difficult to discuss this film, filled as it is with such unflinching ugliness, as a recommendation. But it is also difficult not to recommend a film so confident and coherent in its vision, and so utterly effective in its impact. It should be clarified that there are no real “good guys” in this film. As a textbook example of the revisionist western, wherein good guys and bad guys blend together as shades of grey, this film makes no pretense about its foggy moral complexity and its disturbing view of human nature. Keep in mind something that I mentioned earlier: that the supposed “hero” of our story, within the first fifteen minutes of the film, commits a blatant act of sexual assault. Roy Rogers, this ain’t.

Yet, the film is also surprisingly vocal about matters of conscience, infusing scattered observations about hypocrisy and injustice into its cinematic dna. The film seems to be making sweeping statements of morality such as bystanders who do nothing are never “innocent” or that you can never fully bury your transgressions in the sand. But it does so without allowing the audience the reprieve of a saintly hero. Instead, we get almost the living embodiment of willful vengeance. The premise could be seen as analogous to, “what if a day of reckoning came to certain members of a corrupt society, but instead of a righteous avenging angel who brought justice, it was the Devil himself?” (an analogy further substantiated by the fact that in the film’s final third, The Stranger paints the town blood red and paints the word “Hell” on the entrance sign). Vengeance is at the very core of the film, although on whom and why is not revealed until nearly the film’s final act. But there are hints speckled throughout the narrative that this stranger did not arrive by accident and that every inhabitant’s desperate attempts to control their own fates have merely been the movements of pawns orchestrated by a sinister puppet master.

Not everyone will be on board for this level of moral ambiguity, and rightfully so (John Wayne himself penned a tasteful but derisive letter criticizing the film’s philosophy of humanity and its perspective on the western era of history). But those who can quickly acclimate to this bleak and unyielding revenge tale will likely find themselves highly rewarded, as the film is so effective it almost dares you to try to dismiss it.

As a sophomore effort by Eastwood as a director, the achievement is astounding. He has channeled the muses of both Sergio Leone and Don Siegel, whose works so clearly informed his emergence as a performer, blending both their penchant for grandeur with their haunting storytelling sensibilities. Their names can briefly be seen on the gravestones in the town into which Eastwood’s stranger rides, but it’s only two of many implied ghosts that haunt the tale of the High Plains Drifter. This is a disturbing and provocative film, not to mention powerful, and while its content is likely to distance more than a few audience members, its impact is undeniable.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.

Reed Lackey is based in Los Angeles, where he writes and podcasts about film and faith. His primary work is featured on the More Than One Lesson website and podcast, as well as his primary podcast, The Fear of God (which examines the intersection between Christianity and the horror genre). Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook to receive updates on his reviews and editorials.